To me, ecohydrology is the study of how water and ecosystems interact, at multiple scales, from the microbe and leaf to continental scale watersheds. Over the last twenty years, what is and is not ecohydrology has changed substantially. In fact, five years ago my research would likely not be included within its scope. I appreciate that the field can evolve, incorporating more approaches, as scientists become more interdisciplinary, allowing us to collectively better characterize complex system dynamics underlying our many water resource challenges.

What are your undergraduate and graduate degrees in?

I got my undergraduate degree in Geology from Oberlin College. After a few years of community organizing, I attended Indiana University’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA), earning a MPA in Environmental Policy & Natural Resource Management and a MS in Water Resources. After SPEA, I went on to the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies for my PhD.

How did you arrive at working in/thinking about ecohydrology?

After college I was a community organizer in the northeastern US and for a year worked on urban water quality issues. Working on urban waterways provided me an exciting opportunity to talk about clean water and sense of place, to discuss equity and education, with community members who often didn’t talk to each other. In going to SPEA, I was able to explore multiple dimensions of water resources – lenses ranging from cost-benefit analysis and environmental engineering to stream ecology and ecotoxicology. It was aquatic chemistry with Jeff White that really connected all the dots for me – realizing that by understanding the way elements move through ecosystems I could help address and hopefully answer environmental management problems. To me, the field of biogeochemistry presented this perfect Venn diagram of geology, water, and society; allowing me to answer questions that people cared about.

Ultimately, I am interested in how human induced disturbance – from the chronic pushes on ecosystems (e.g. warming temperatures) to acute events (e.g. fires) – alters the way carbon and nitrogen cycle through watersheds. In order to answer any of these questions we need to understand how the water is moving through the ecosystem and how disturbance changes the partitioning of water in that system. As my research program has evolved, I have thought more explicitly about the shifts in flow paths accompanying disturbance and how these changes ultimately alter the connectivity of the terrestrial and aquatic landscape.

What do you see as an important emerging area of ecohydrology?

I am really interested in all the work going on linking hydrologic variability (on scales of minutes to months) with ecosystem processing and not surprisingly biogeochemistry. Whether said variability is driven by diurnal fluctuations in evapotranspiration, tides, dam operations, or the decadal plus variability of climate and vegetation, we can apply lessons learned from seemingly disparate systems, more easily if we use an interdisciplinary framework like ecohydrology. These lessons should help us better understand not only how ecosystems function but also how to better address growing water resource challenges.

The rollback of WOTUS in the past year sparked significant advocacy by hydrologists and I am excited about the engagement of our field in the public sphere; especially given how science is under attack. This engagement is especially important given the centrality of clean, available water in equity issues globally and I am cautiously optimistic that we are becoming more comfortable in our role as advocates.

Do you have a favorite ecohydrology paper? Describe/explain.

Recently I’ve been really excited about the papers coming out of the Dry Rivers RCN group because their synthesis and opinion pieces collectively connect how our science can and should inform policy and management. Two such papers include (1) Zero or not? Causes and consequences of zero-flow stream gauge readings (Zimmer et al. 2020) discussing various scenarios that can lead to no flow conditions and the importance of thinking about context and (2) An Eos piece (Shanafield et al. 2020) on the need for community engagement in river management, especially important given the increased risk of drought and ecological degradation. In addition, the nature of the RCN really highlights what we can learn when examining mechanism across broad spatial scales, something that is invariably more successful via collaborative interdisciplinary groups.

What do you do for fun (apart from ecohydrology)?

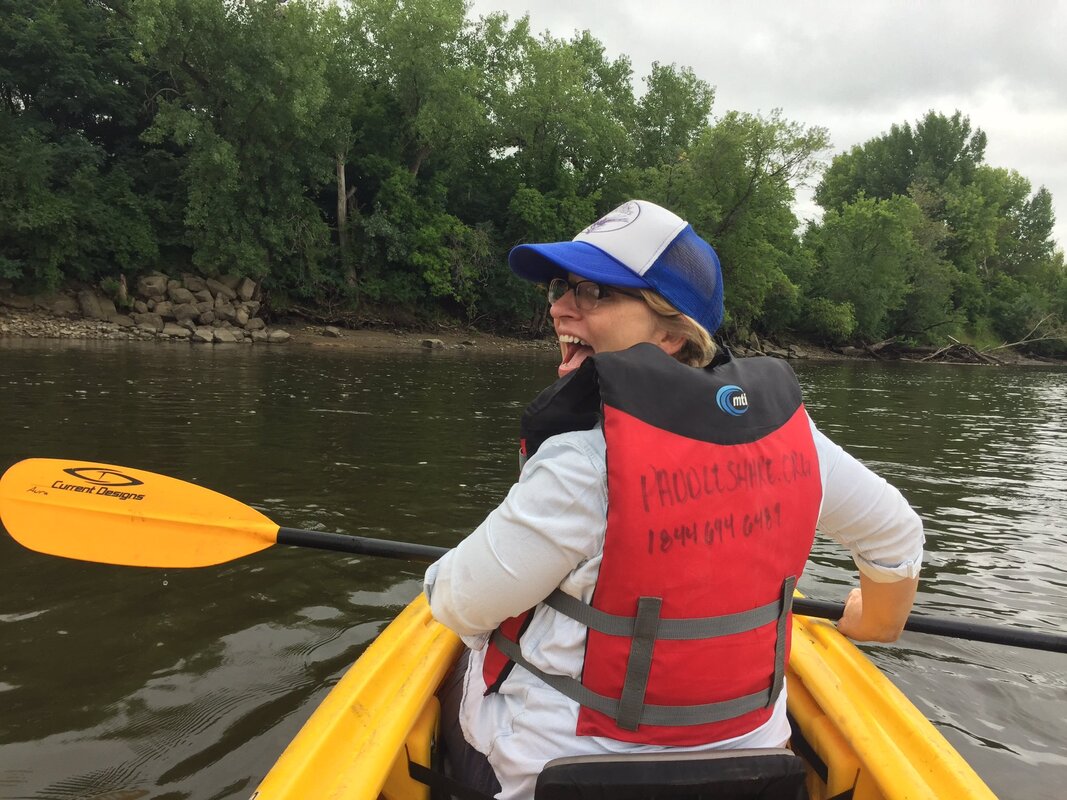

I am lucky enough to live in a place where I can hike, year-round, for miles from my doorstep. I am grateful for this geography and take advantage of it as much as possible. In addition, I enjoy other very “on brand” watery activities like snowshoeing, kayaking, and canoeing. When not soaking in the 300 days of sunshine offered by Colorado, I enjoy crafting, gardening, and cooking with my two kitties and new pandemic puppy (and hopefully friends again in the not too distant future!).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed